Friday 15 November 2013

The nesting of EAGLE within Pelagios

Thursday 14 November 2013

The EAGLE flies with Pelagios

- To make all content available in Europeana, the largest culture and heritage aggregator in Europe (#AllezCulture)

- To use Wikidata for our translations of inscriptions. By gathering all existing translations of inscriptions and providing an easy-to-edit online database of translations, EAGLE aims to enrich both those data that are present in Wikimedia Commons with curated content from the databases, and the database contents themselves with contributions from the wider public

- To produce an open, interoperable format. In the Eagle portal, data will be available in XML files compliant with EPIDOC/TEI guidelines.

- To produce open vocabularies that align existing models used by single content providers. These will provide many other URIs which, we hope, will become a way to further connect other data on the basis of Object Type, Material, Type of inscription, to mention just some.

Thursday 17 October 2013

IWP2: Pelagios and the Beakers of Vicarello

The last few weeks have been a busy time for the Pelagios team. In parallel to kicking off our work on linking gazetteers as part of first Infrastructure Workpackage (IWP 1), we also started to assemble some foundational bits and pieces of our second IWP - which is concerned with building up the data and annotation infrastructure.

Prelude: the Itinerarium Gaditanum

Jump cut to Vicarello, Italy, mid-19th century: excavations at the Aquae Apollinares Baths in 1852 reveal three cylindrical vessels made of silver, with heights varying between 95-153 mm. Excavations in 1863 later reveal a fourth vessel of similar kind. Although differing in the details, on the surface of each vessel is engraved the Itinerarium Gaditanum, the land route between Gades (Cadiz) and Rome, listing between 104 and 110 road stations along the way, and the distances between them in units of Millia Passum (thousand Roman steps or 1481 meters approx).

The Vicarello Beakers, as they are now frequently referred to, have traditionally been identified as miniature replicas of a milestone probably erected in Gades, perhaps similar in design to the Miliarium Aureum (the Golden Milestone) in Rome. Originally, through the study of the different stations of the route, experts had dated them at different times between the governments of Augustus and Tiberius. But recent palaeographic studies and comparisons with late documents such as the Antonine Itinerary or Burdigalensis Itinerarium, as well as their resemblance to the missorium of Theodosius suggest a dating to the late third or early fourth century AD.

Their handy number of toponyms, as well as the fact that there are images and transcriptions available online already, makes the Vicarello Beakers an excellent test case to teach our data infrastructure a few new tricks. Technical details about the upgrades it's about to receive (complete with RDF samples and pointy brackets) will appear on our Wiki and through our mailing list in due course. But, for the purpose of this blog post, let me just give you a sneak preview of some of the things our upgraded data model can do.

Linked Data, Open Annotation, RDF, What?

You may recall that Pelagios is based on the principles of Linked Open Data, and that we have chosen the Open Annotation Data Model as the conceptual basis for our common vocabulary. These foundations will not change. But with a growing network of partners, more diverse content, and increasing amounts of data, it has become painfully clear that our initial data model from the days of Pelagios 1 and 2 has reached its limits. We have grown to so many partners and content now that data for major places has become practically unmanageable - just try to find something useful in our data about Rome!

So what are the things our new data model will improve?

- First and foremost, our new model allows for richer item metadata. There is now a much cleaner separation between information about the item, and information about the places that relate to it (and how). There is room to encode dates and temporal characterics, categories, authorship, languages used in the source document - ordering dimensions which help us to get more structure into the pile of "anonymous place references" we agglomerated through our first two project phases.

- In line with a richer metadata model, we have also adopted the FRBR distintion of Work and Expression. In FRBR terminology, the Vicarello Beakers are a Work - "a distinct intellectual or artistic creation". Each of the four beakers is termed an Expression of this Work. This is another straightforward ordering principle, which helps us to get more structure and hierarchy into our data.

- One of the changes that happend in the transition between the (now deprecated) Open Annotation Collaboration model and the new Open Annotation model is support for multiple "annotation bodies". I'll refer to the OA spec for details. But as far as Pelagios is concerned, this change allows us to represent the different "faces" of a place reference in a source document - logical mappings to (a) gazetteer URI(s), its precise transcription, different images of it, etc. in a much simpler way.

- Toponyms in a document may follow a certain sequence or layout. The Vicarello Beakers are a prime example of this: laying out their toponyms in a list with four columns, according to the sequence of the places along the route between Gades and Rome. We're experimenting with ways to record the logical ordering of toponyms in a document, and bringing it to use for visualization.

This simple mashup shows the toponyms from the four Vicarello Beakers on a map. There's an information box with the Work metadata at the bottom, and if you look to the top-right, you will find a small layer menu which lets you switch places - and the path indicating the toponym sequence - on and off individually for each beaker. Click on a place, and a popup will show you the transcription from the Beakers, along with the gazetteer reference from Pleiades, which corresponds to the place.

What's noteworthy about this demo, however, is not so much the map itself - but rather that the map is generated completely automatically from a Pelagios RDF file, containing item metadata and OA annotations. (You can grab the RDF source file here.) In essence, these are also our first baby steps towards the Visualization Workbench - which is the objective of our third infrastructure workpackage.

In the meantime, stay tuned for the exciting sequel to "Pelagios and the Beakers of Vicarello" - in which the Pelagios team will tackle their next Early Geospatial Document, and where we will shed some light on the workflow we use to compile our data, and how we transform it to Open Annotations.

Tuesday 8 October 2013

New Researcher Joins the Team

Tuesday 1 October 2013

A Web of Gazetteers

Pelagios is all about creating connections between places and data about them. Since we are now in the process of extending our scope beyond the ancient Greco-Roman world, we have been joined by two new infrastructural partners - PastPlace and the China Historical GIS. They will provide us with records for those places that are beyond the spatial or temporal coverage of our long-term partner in crime, the Pleiades Gazetteer of the Ancient World.

Moving from a single gazetteer to a system of three has significant consequences. Gazetteers vary widely in how they represent places conceptually and syntactically: with different abstractions, relations and hierarchy models; with different approaches to express changes over time, or to record the source or bibliographic references that lead to the inclusion of the place in the gazetteer. In fact, even the definition of what a place is can radically differ from one gazetteer to the next. This is especially true for the specialist gazetteers that we are dealing with in the humanities.

The goal of our first infrastructure work package is to bridge these gaps and create a framework to link up our gazetteers to form a coherent whole. Obviously, we can (and will) never find the one generic datamodel that fits the needs of everyone, and that every gazetteer should adhere to from now on. Apart from practical issues of implementation and migration effort, such a model would inevitably end up being either hugely complex (because it would need to subsume all the complexities and subtleties of each gazetteer known at the time of design); or it would be overly simplistic (because it would force everyone into a rigid, trimmed-down schema, sacrificing the richness and specialization of the original custom models).

For this reason, we are not aiming to create a common data model in the first place. Instead, we're following our general strategy of "connectivity through common references", which standardizes how to create links between stuff, rather than standardizing how stuff should be represented. That being said: things don't work entirely without any data (or, rather, metadata) specification at all, unfortunately. What we do standardize in our case is a syntax for "descriptive records". Each gazetteer exposes such records about each of its primary entities, and they contain the absolute minimum information we need in order to:

- identify and disambiguate places, and

- build a searchable index external to the gazetteer, so that we can relate search queries in a third-party application (such as the Pelagios API) to the original entry in the source gazetteer.

The other essential aspect that we need in order to move from a single gazetteer to a system of many is (surprise surprise!)

links. Each descriptive record may (and should) include links to entries in other gazetteers in order to indicate similarity.

(We are going to use the semantics of skos:closeMatch, which

is defined as a relation "[...] used to link two concepts that are sufficiently similar that they can

be used interchangeably in some information retrieval applications".) Specifically, we encourage gazetteers to include links

to one or more reference gazetteers in their descriptive records - open data gazetteers with global coverage,

high community adoption, and a Linked Data representation - such as Wikidata or

GeoNames.

And what's the result of this? Answer: a dense network of links that makes our specialist gazetteers globally navigable, as well as re-usable and combinable in other contexts and applications. We are still in the process of polishing the spec for our descriptive records. You can find the current status on the Pelagios Cookbook Wiki. Our partners are about to start working on the implementation; and I'm about to extend our core data handling software libary to support it as well.

Are you working with a gazetteer dataset you want to see linked up with Pelagios? Let us know - we'd be excited to see a global Web of gazetteers grow and flourish!

Tuesday 24 September 2013

Pelagios 3 Overview

Mission

The mission of Pelagios 3 is to annotate, link and index place references in digitized Early Geospatial Documents (EGDs). EGDs are documents that use written or visual representation to describe geographic space prior to 1492.Primary objectives:

(i) provide an index of toponyms attested, and the places they refer to (where known), in all available EGDs, accessible both as Linked Open Data and via the Pelagios Web Service;(ii) create an open and semi-automated toolset that allows the scholarly community to enhance and refine the index incrementally, by annotating place references in further historical sources;

(iii) develop a freely available analysis workbench and contextualization widgets that enable researchers to bring together spatial documents in new and innovative ways and provide key contextual information as embedded content in third-party websites.

We will carry this out through a series of nine workpackages. Three Infrastructure Workpackages (IWPs) will deal with the mechanics. Six Content Workpackages (CWPs) will deal with content related to specific historical regions and periods.

Workpackages

IWP1: Gazetteer Infrastructure

IWP1 will establish the common gazetteer infrastructure necessary to form the bodies of Pelagios annotations. Pelagios is grounded in the idea of a “Gazetteer ecosystem”: URI-based gazetteers that are specific to a spatial, temporal or cultural milieu and maintained and curated by their respective research communities, but aligned through the principles of Linked Data and a common, overarching referencing framework. (Hereafter we refer to all such URI-based gazetteers simply as ‘gazetteers’). In order to arrive at an initial, pragmatic version of such an infrastructure, two challenges need to be addressed: (i) a common, generic gazetteer data model needs to be identified which suits the needs of the different individual stakeholders involved; (ii) referencing frameworks need to be agreed, through which different gazetteers can cross-link to each other.IWP2: Annotation Toolkit

IWP2 will facilitate pragmatic solutions to the issues of transcription and identification by assembling a toolkit of both automated and manual methods and technologies that can be tailored to a specific document. The following software tools will be the results of IWP2:- an assistive image processing tool that automatically pre-identifies toponym candidates on digitized old maps;

- a tool (integrated with the previous browser interface) to visually enhance pre-identified toponym candidates to aid manual transcription;

- manual annotation and transcription tools that focus specifically on simplifying navigation and selection within high-resolution digitized EGDs;

- a recommender system that proposes plausible toponym options to the annotator (seamlessly integrated with the overall annotation browser interface);

- a management dashboard to extract, compile, edit and export lists of annotations, and prepare them for linking and upload into the Gazetteer infrastructure;

- a publishing tool to present annotated items online.

IWP3: EGD Workbench

IWP3 will develop tools that allow end-users to navigate, visualise, interpret and compare the annotations generated in CWP1-6. These tools will operate on top of the Pelagios API, which will be extended to support the updated Pelagios 3 annotation data model. Concrete visualization software components to be developed will include:- a browser interface containing a synchronized map-, timeline-, and network-based visualization;

- a tool to drill down to explore specific properties of an annotation set (equal to one or more collections or specific EGDs), such as its spatial coverage or the sequence of the toponyms contained within it, and compare it against other annotation sets.

- a visual search interface which enables end users to discover collections that are particularly salient with regard to a specific area and time of interest.

CWP1: Latin Tradition:

Example EGDs - Antonine Itineraries, Ravenna Cosmography, Bordeaux Itinerary, Vicarello goblets, Natural History (Pliny), Chorographia (Pomponius Mela), Peutinger Table, Divisio Orbis Terrarum, Dimensuratio provinciarum, Notitia Dignitatum, Ora Maritima (Avienus), Periegesis (Priscian), De Mirabilibus Mundi (Solinus)CWP2: Greek Tradition:

Example EGDs - Geography (Strabo), Armenian Geography, Suda, A Sketch of Geography in Epitome (Agathemerus), Manual of Geography (Ptolemy), Description of Greece (Pausanias), Synecdemus (Hierocles), Christian Topography (Cosmas), Epitome of the Ethnica (Stephanus of Byzantium), Description of the Roman World (George of Cyprus), the Madaba Mosaic, The Dura Europos Shield, the Iliad, the Odyssey, texts in Minor Greek Geographers vols. 1 & 2.CWP3: Early Christian Tradition

Example EGDs - Gough Map, Italie Provincie Modernus Situs, Description of the World (Marco Polo), On the Vicissitudes of Fortune (Niccolo de Conti), Fra Mauro Map, Erdapfel (Martin Behaim), World Map (Henricus Martellus Germanus), Genoese Map, De Virga world map, Vesconte World Map, Bianco World Map, approx. 320 sundry EGDs from the British LibraryCWP4: Early Maritime Tradition

Example EGDs - Le Liber (portolano), Lo Compasso (portolano), approx. 180 Portolan charts (Pujades 2007), Catalan Atlas (Cresques Abraham).CWP5: Early Islamic Tradition

Example EGDs - Image of the Earth (Al Khwarizmi), al-Kashgari World Map, Tabula Rogeriana (al-Idrisi) Book of Curiosities, Maps of the Balkhi SchoolCWP6: Early Chinese Tradition:

Example EGDs - Yujitu (‘Map of the Tracks of Yu’), Songhuiyao, Chinese Buddhist Temple Gazetteers, ‘Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms’Monday 16 September 2013

Pelagios Chapter 3: Early Geospatial Documents

With a digital place index of maps and descriptions of the world in place, researchers and the general public will be able to explore online the historical significance of both famous and obscure places in the history of geography. As just one example, Claudius Ptolemy used London as one of his primary reference points for global time zones in the late second century, just as we do today. While such coincidences may be rare, and many places in early maps and texts are unidentified, or existed only in the popular or religious imaginations, our aim is to help their rich biographies to be told. With such an unprecedented variety of data linked together, it will be possible to trace in broad terms the continuities - and discontinuities - of people's responses to the world around them. Equally exciting, and thanks to the continuing annotation of data by Pelagios growing community of partners, you'll also be able to bring together disparate fragments of its life history, its connections with other places, its stories and imagery.

Tuesday 3 September 2013

How Dickinson College Commentaries linked up with Pelagios

DCC explores a model of textual commentary that tries to take full advantage of the digital medium, harnessing the best of traditional philological, historical, and archaeological scholarship, and focusing on the user experience in a way to enhance reading, rather than just searching. We’re not really a database, but a reading environment, so we try not to bury the user in information, but to offer scholarly guidance informed by teaching experience. We also have some limitations financially and institutionally. We are lucky to have an endowment at the Department of Classical Studies at Dickinson, on which we can draw to hire undergraduate students. And we have a strong support system in the Academic Technology unit at Dickinson, where Ryan Burke built the structure of our site in Drupal, and helps to maintain and improve it. But we have no graduate students, no dedicated programmers or web developers, and no full time staff. I teach a full load at Dickinson and do this in my spare time, as it were, with help of a number of colleagues at other institutions who are on our editorial board. This is all to say that I have to be careful about not getting in over my head when it comes to site maintenance. I value user functionality and solid content above all, but simplicity runs a very close third.

Pelagios, with its machine linking of places mentioned in our commentaries to the unique place identifiers in Pleiades, delivers simplicity itself. On our end what needed to be done was to create a single file that listed all of our geographical annotations, with their locations (urls). We already had Google Earth maps made in summer 2012 by Dickinson student Merri Wilson, that contained placemarks with all places mentioned in two of the existing commentaries, each placemark annotated with Pleiades URIs (unique identifiers). A third Google Earth map, for Caesar’s Gallic War, did not have the Pleiades URIs, and all the linkages in the other two commentaries (Sulpicius Severus’ Life of St. Martin and Book 1 of Ovid’s Amores) had to be checked for errors. Archaeology and Classics major Dan Plekhov was perfect for this job, which required a good knowledge of ancient geography, Latin, Greek, and solid research skills. He worked in Carlisle for 8 weeks in the summer of 2013, with approximately two weeks devoted to this aspect of the project.

Meanwhile, computer science major Qingyu Wang investigated the .RDF format we were to use for the comprehensive file, and the very specific formatting required by Pelagios. This is not exactly the kind of thing computer science majors do all day, but she taught herself the skills she needed to complete the work, spending about a week on it all told. She was aided by good advice from Sebastian Heath at New York University, and Rainer Simon of Pelagios. We had to invent a human-readable code for our specific type of annotations—so we could keep track of things and every annotation would have a unique designation—then put all that into a format that Pelagios could deal with. My role was deciding on concise but informative conventions that fit our material. Once we figured all that out, Qingyu created the .RDF file that specifies the linkages between a unique ancient place as referred to in Pleiades, with a specific annotation on a page of our site. Now, when you go to that place in Pleiades (Gallia, for instance), under "Related Content from Pelagios" you will see "Pleiades urls Dickinson College Commentaries." So someone exploring Gaul could now go straight to DCC, read Caesar’s account, or watch our little video of the famous opening paragraph of the BG.

Here are some examples of the lists of references we adapted from the Pelagios template. The first is a reference to the Alps in Sulpicius Severus' Life of St. Martin, section 5.

<rdf:Description xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#" xmlns:h="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xmlns:rdfs="http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#" xmlns:oac="http://www.openannotation.org/ns/" xmlns:dcterms="http://purl.org/dc/terms/" rdf:ID="sulpicsev-martin-5.4-alpes">

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.openannotation.org/ns/Annotation"/>

<oac:hasBody rdf:resource="http://pleiades.stoa.org/places/783"/>

<oac:hasTarget rdf:resource="http://dcc.dickinson.edu/sulpicius-severus/section-5"/>

<dcterms:creator rdf:resource="http://dcc.dickinson.edu/"/>

<dcterms:title>"Sulpicius Severus, Life of St. Martin 5.4"</dcterms:title>

</rdf:Description>

The Gallic tribe the Boii in Caesar, Gallic War 1.5:

<rdf:Description xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#" xmlns:h="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xmlns:rdfs="http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#" xmlns:oac="http://www.openannotation.org/ns/" xmlns:dcterms="http://purl.org/dc/terms/" rdf:ID="caesar-bg-1.5-boii">

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.openannotation.org/ns/Annotation"/>

<oac:hasBody rdf:resource="http://pleiades.stoa.org/places/197173"/>

<oac:hasTarget rdf:resource="http://dcc.dickinson.edu/caesar/book-1/chapter-1-5"/>

<dcterms:creator rdf:resource="http://dcc.dickinson.edu/"/>

<dcterms:title>Julius Caesar, Gallic War 1.5</dcterms:title>

</rdf:Description>

Mt. Olympus in Ovid, Amores 1.2.39:

<rdf:Description xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#" xmlns:h="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xmlns:rdfs="http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#" xmlns:oac="http://www.openannotation.org/ns/" xmlns:dcterms="http://purl.org/dc/terms/" rdf:ID="ovid-amores-1.2.39-olympusmons">

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.openannotation.org/ns/Annotation"/>

<oac:hasBody rdf:resource="http://pleiades.stoa.org/places/491677"/>

<oac:hasTarget rdf:resource="http://dcc.dickinson.edu/ovid-amores/amores-1-2"/>

<dcterms:creator rdf:resource="http://dcc.dickinson.edu/"/>

<dcterms:title>"Ovid, Amores 1.2.39"</dcterms:title>

</rdf:Description>

Our full .rdf file is available here.

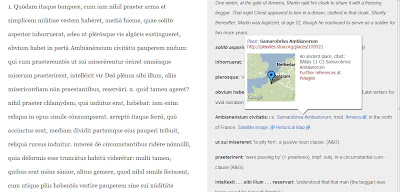

Another aspect of that process, in a sense the reverse of it, was the automatic channeling of data from Pleiades into DCC, via the addition of thumbnail pop-ups on the names of places mentioned in the notes fields. As of this summer, when you mouse over such a linked place name in DCC, a thumbnail with a small map pops up, with the link to Pleiades.

The beauty of this is that one does not have to navigate away from the text to get an idea of where roughly the place is; but at the same time, Pleiades is only a click way. Qingyu and Ryan Burke made this happen, using a bit of css code created by Sebastian Heath for use in his ISAW papers. One nagging issue is that when viewed on an iPad, the pop-ups do not go away, and one must reload the page to get rid of them. But I view this is a superb use of the digital medium to enhance the reading experience. Geographical knowledge is delivered on time, as needed, unobtrusively, right there beside the text, in way simply impossible in print. And all that is required, once the css code is in place, is to create the normal html link in the Drupal editor.

I’m here at a liberal arts college doing digital humanities at a fairly small scale, compared to what’s going on at large research universities, or at a well-funded outfit like the Perseus Project. Small size has certain advantages, I suppose, but the biggest danger is probably isolation. On an organizational level I try to avoid that by reaching out to colleagues at other institutions and getting them involved, as the Bryn Mawr Classical Review has done so successfully. But Pelagios offers DCC and projects like it an equally potent way to combat isolation, by allowing our small project to make a contribution to the much larger world of linked geographical data. Maybe someday there will be a similar infrastructure of sharing linked data about ancient persons, texts, and material objects as well, and I’d like to be there adding to it.

Chris Francese (francese@dickinson.edu)

Monday 1 July 2013

A SQL version of the Pleiades dataset

For those of you who use the Pleiades data in your applications I’ve created a .sql file for their newest data dump which you can find here. I used the Pleiades data dump from June 27, 2013. What’s nice about the Pleiades people is that when they say a file is comma separated it really is. I downloaded this file and extracted it into the promised .csv and then imported it directly into Excel where I formatted it into a set of .sql inserts. The columns seem to have changed somewhat from the previous versions; there are fewer name columns. As a result I reformatted my Pleiades data table in SquinchPix’s database so that it now looks like this:

CREATE TABLE `PlacRefer` (

`bbox` varchar(100) default NULL COMMENT 'bounding box string',

`description` varchar(512) default NULL COMMENT 'Free-form text description',

`id` varchar(100) default NULL COMMENT 'Pleiades ID number',

`max_date` varchar(255) default NULL COMMENT 'last date',

`min_date` varchar(100) default NULL COMMENT 'earliest date',

`reportLat` float default NULL COMMENT 'Latitude',

`reportLon` float default NULL COMMENT 'Longitude',

`Era` varchar(24) default NULL COMMENT 'Character indicate the era',

`place_name` varchar(100) default NULL COMMENT 'Name string for the place'

);

I formatted the bounding box as a comma-separated varchar. I do this because the bounding box requires special treatment; it might be missing altogether or it might be less than four points so, if you’re working with it, just get it into a string and split the string on commas. Then you’ll have an array of items that you can treat as floats. I finally got it through my thick skull that the description line can be parsed into keywords so I’ll be using that more in the future. The ‘id’ field is the regular Pleiades ID. Is it my imagination or did the Pleiades people suddenly get a large dump of data from the Near East? The number of items in the file is now 34,000+ and this looks like a big increase. The max_date and min_date fields give the terminus ante quem and terminus post quem, respectively, for any human settlement of the place in question. The reportLat and reportLon fields haven’t changed. The ‘era’ field gives zero or more characters that indicate the period of existence of any site: ‘R’ for ‘Roman’, ‘H’ for ‘Hellenistic’, etc. I included them because it might be handy for your chronological interpretation. The ‘place_name’ field is the only name field in the current setup.

If this table layout is satisfactory for you then you can get all the Sql to create and populate the table with all the newest Pleiades data from Google Drive here. Be careful; this new .sql deletes the PlacRefer table first.

I modified my Regnum Francorum Online parser to use this renewed table. The relevant code looks like this:

$place_no = $l5[0]; // $l5[0] is a fragment of the input record which contains the // Pleiades ID.

unset($lat); // we test for unset later

unset($lon);

$querygeo = "select a.reportLat, a.reportLon from PlacRefer a where a.id = $place_no;";

$resultgeo = mysql_query($querygeo);

$rowgeo = mysql_fetch_array($resultgeo);

$lat = $rowgeo[0];

$lon = $rowgeo[1];

This is how you’ll probably use it most of the time – using the Pleiades ID to retrieve the lat/lon pair. I was pleasantly surprised at how much the data has improved. I redid all the Regnum Francorum Online records with the new data and it looks a lot better. So congratulations to the Pleiades guys! Although they should double check the exact location of Nördlingen. Here's how the first 500 Regnum Francorum Online records look on a map.

|

| First 500 Regnum Francorum Online records displayed on SquinchPix using new Pleiades data. |

If you want to do this yourself from the original Pleiades data dump then be sure to convert (no parentheses in the following sequences) all double quote characters to (") , left single quote to (‘) and right single quote to (’). The data has elaborate description fields which have been formatted with lots of portions quoted in various ways by various workers. Also many place names in the Near East and many French names contain embedded single quotes that must be changed to (‘) or (’) or the equivalent. If you need a guide go here.

Get this right first because if you’re not absolutely sure that you’ve got all the pesky quotes taken care of then the sql import won’t run.

But you can avoid all that hassle by just downloading my .sql file from Google Drive and importing it to your DB. Have fun!

Robert Consoli

Cross-posted from Squinches.

Thursday 27 June 2013

A New Dimension for Pelagios

Thursday 25 April 2013

How Ancient History Encyclopedia linked up with Pelagios

We're back for some information on how we linked Ancient History Encyclopedia to Pelagios. I hope that this can be of help for future websites that join this excellent project.

We're back for some information on how we linked Ancient History Encyclopedia to Pelagios. I hope that this can be of help for future websites that join this excellent project.First of all, we need to explain how AHE works. The website is entirely based on tags / keywords. Each tag has one (and only one) definition associated to it, and many possible articles, illustrations, or timeline events. It is possible --and indeed necessary for the website to work properly-- that articles, illustrations, and timeline events are linked to many tags. An article on "Trade in Ancient Greece" would be tagged with "Greece", "Economy", "Trade", "Colonization", and it would subsequently be listed under all those tags' pages.

Now the initial idea was easy: Let's link up every geographical tag of ours (cities, countries, regions) to its equivalent location in Pleiades. We've got 2,400 tags, and we expect to have many more in the future, so we didn't want to do this all by hand. Instead, we wanted something future-proof, that would notify us automatically of possible matches between tags and Pleiades locations.

Every day, we automatically import the Pleiades database of names, their respective location IDs and their locations and mirror it in our database using a cron job. We wrote a nifty little PHP function that converts the Pleiades data to a PHP array -- feel free to use it.

In our editorial team's interface we have a page that automatically tries to find possible matches between Pleiades place names and tags on AHE. For links, we only look at those tags which have a definition -- after all we only want to link up content that is of use to potential readers, not empty tags. Editors can then review the link suggestions and either approve or reject them. That way, we already found most of the links between our datasets.

|

| Suggestion from the automatic linking script |

Then there is the problem of links that aren't found by our automatic matching script. For example, on AHE the tag is called "Greece" whereas on Pleiades it's known as "Hellas". Another example would be "Mediterranean" on AHE is known as "Internum Mare" at Pleiades. No script can figure that out!

For those cases, we added another functionality to our tag editor form: Our editorial team can simply search the Pleiades DB mirrored on our server for links, for each tag. An editor could for example see the tag "Greece", notice that it's not linked to Pleiades, open the linking form for the tag Greece and manually search for "Hellas".

|

| Tag listing for editors (2nd last column is the Pleiades link) |

When a tag is linked, we write the Pleiades ID into a newly-created field in that tag's entry in our database (hoping that Pleiades will never change tag IDs).

Now it's time to deliver all this data in a format that Pelagios can understand. We have another script that goes through all the linked tags and fetches their respective definitions, as well as all articles and illustration that are linked to them in our database. Then we output each tag definition as Turtle/RDF in the Pelagios format, linked to a specific Pleiades ID. All articles and images associated with that tag are also output for that Pleiades ID. The final result looks like this. Notice that while each definition only occurs once (one definition per tag), articles and images can appear multiple times, linked to multiple tags (as one article or image is linked to many tags).

Personally, I find that Turtle/RDF is somewhat mindboggling and not exactly easy to understand (I'm not a professional programmer), but with the excellent help of Simon Rainer, Elton Barker, and Leif Isaksen we managed to make it work and validate. Thanks a lot guys... we couldn't have been able to do it without you!

We then submit the generated file to Pelagios (in the next version of Pelagios it'll be imported automatically on a regular basis).

I hope that this was helpful or at the very least interesting to anyone who is looking to link up with Pelagios. If your site is similar to ours, do feel free to drop us a line on {editor AT ancient.eu.com}! We're always happy to help!

Monday 8 April 2013

Ancient History Encyclopedia joins Pelagios

Our mission is to make people interested in ancient history; we want to engage our global audience, by not only presenting the facts but also by doing it in an interesting way. We believe that "story" is a key component in the word "history", and we aim to convey in all our published content our belief that history is the greatest story ever written.

Despite being a story, history is not linear (as it is taught in most school coursebooks), but rather a very parallel type of story, where everything is interlinked. This is why digital media are much better-suited to history education than books of the dead-tree type (which we still love, of course). At AHE pieces of information are tagged and shared across different but related subjects, and each page is built automatically, taking precisely the information that is relevant for that subject from our database of definitions, articles, events, and maps.

|

| Interactive Map of the Ancient World (WIP) |

Many high schools and undergraduate college courses around the world point to AHE in their reading lists or use it for course material. Our mission is to let everyone learn about ancient history in an engaging and easy-to-understand way. We want our readers to get excited about ancient history, and then we want to point them to the more detailed, academic, or original sources (both on our site and across the internet).

Joining Pelagios is simply the next logical step: The more history we manage to link together, the more our readers can "dig deeper" and get lost in ancient times. The easier it is for students to find the vast amount of material that all Pelagios contributors have assembled, the better. We are very excited to be part of the vast network of data coming from high-quality websites and established institutions alike!

New Pelagios Partners: DM Project

DM is an on-line environment that allows users to easily assemble collections of images and texts for study, produce their own rich data, and publish digital resources for individual, group or public use. At its most basic, DM is a tool for linking media - a suite of tools that enables users with little technical expertise to mark regions of interest in manuscripts, print materials, photographs, digital texts, etc. and provide searchable annotations on these resources and the relationships among them. A user may create links between any combination of resources (images, texts, and selected regions of images or texts as marked out by a user). The most common is a link from a textual annotation to the image, text, or selected region it describes, but a single annotation may also reference (e.g., for comparison) selections from several images and/or texts. Today, DM is being used by a number of projects, from long-term scholarly initiatives, to collaborative research, to individual scholarship. In addition to such use-cases, we are collaborating with the Stanford University’s Digital Medieval Manuscript Initiatives and the SharedCanvas project, as well as other partners and projects at Stanford, the University of Toronto, Johns Hopkins University, Yale University, the British Library, St. Louis University, and Los Alamos National Lab, among others.

Our current phase of development is funded by a multi-year Digital Implementation Grant from the NEH. During this work, we will be focusing primarily on the ability to: A) create and manage collections of images and texts; B) add the ability for users and groups in order to create, track and organize work by different collaborators within a working group; C) easily "roll out" the linked and annotated data created within the DM environment to a wide array of standard publishing formats (e.g. for automated and updatable display within Omeka, MediaWiki, and similar platforms); and D: developing Virtual Mappa with the British Library, a pilot environment of historic maps hosted by multiple repositories, where users may create linked environments of annotations for individual, collaborative, and educational purposes.

In late April / early May 2013, DM will be rolling out a new version of the resource, with new features for working with multiple collections of on-line images, as well as improved functionality for managing workflow, navigation and annotation. A sneak peek at some of the functionality is available on our project website, which also contains information about the project's history, its partners, and its current goals: http://dm.drew.edu/.

Regards,

Martin Foys & Shannon Bradshaw

================

DM Project

Co-Directors: Shannon Bradshaw, Associate Professor of Computer Science &

Martin Foys, Associate Professor of English (Drew University)

Contact: dm@drew.edu

Website: http://dm.drew.edu/

Friday 18 January 2013

The “Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World” joins Pelagios

NOTE: A more "technical" report will follow soon.